Naturalists’ World

Last Week in Nature

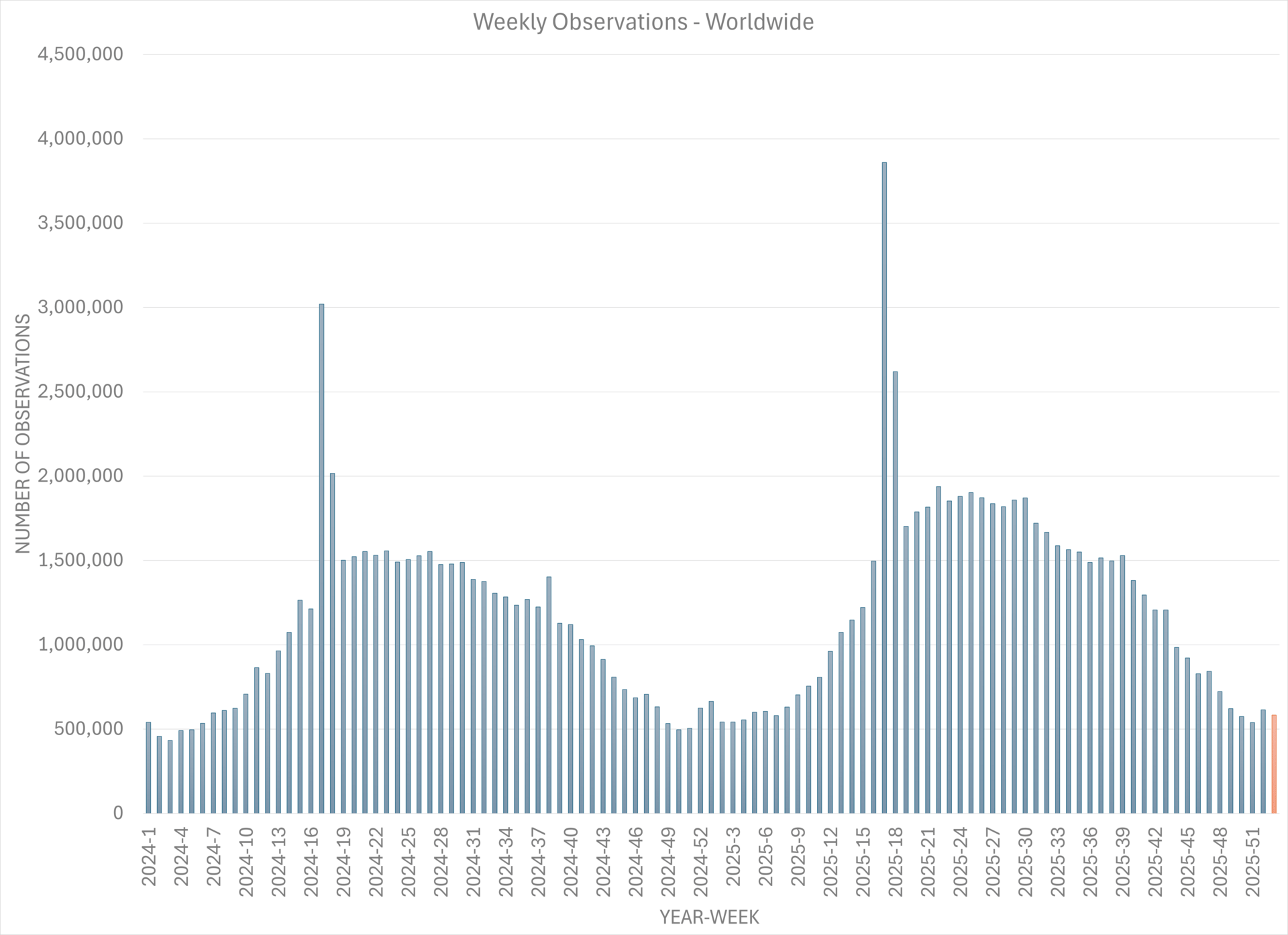

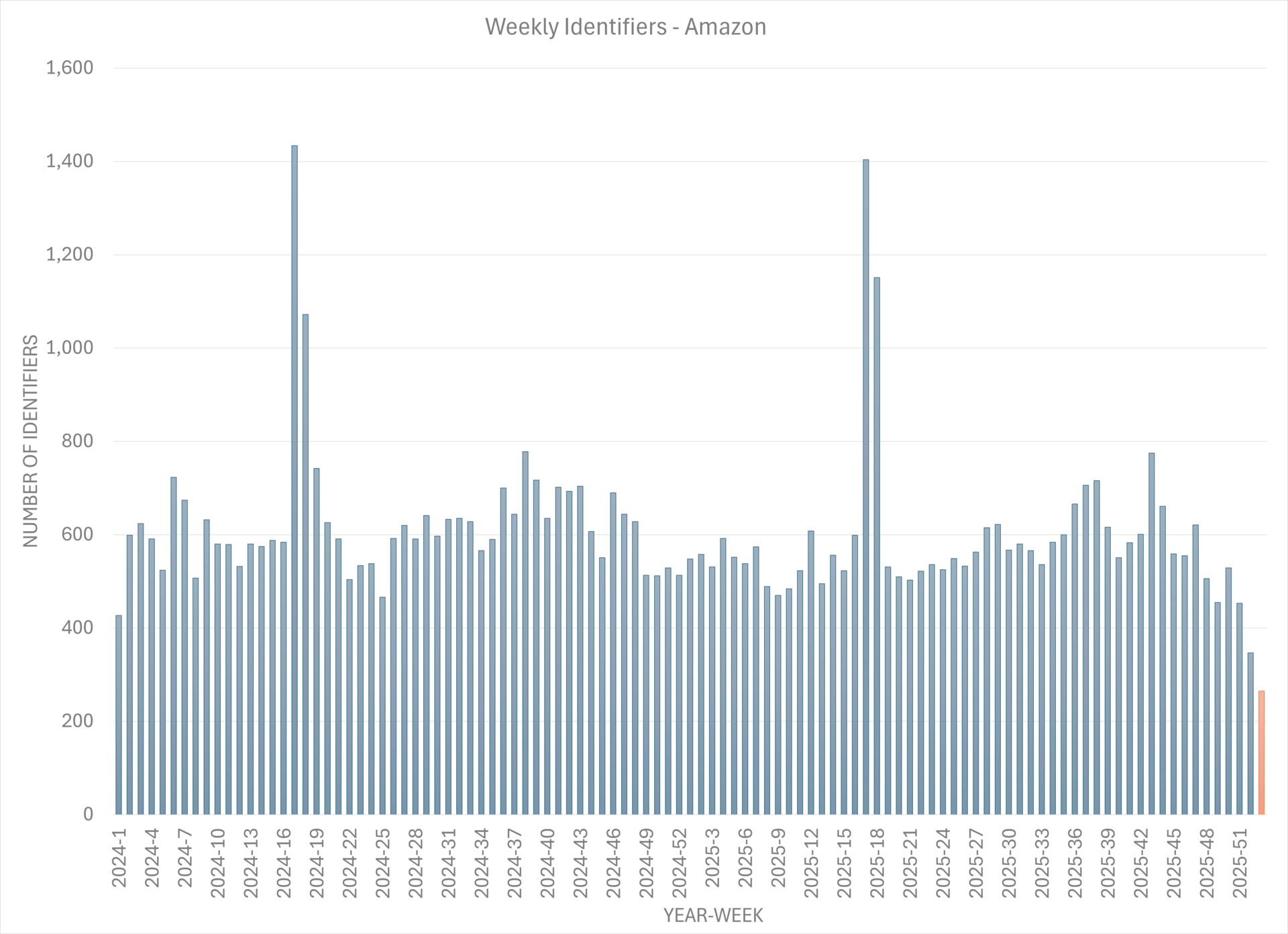

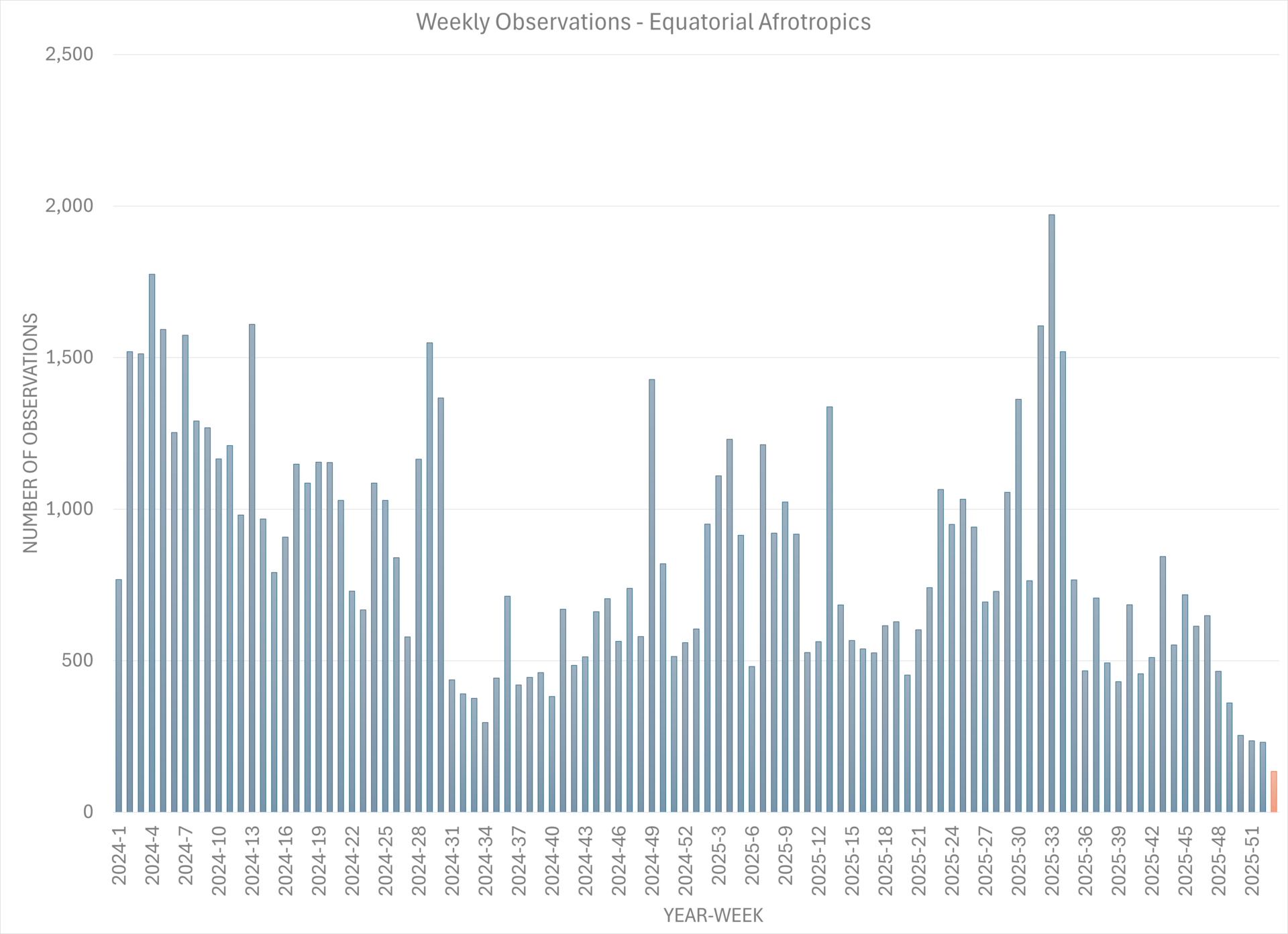

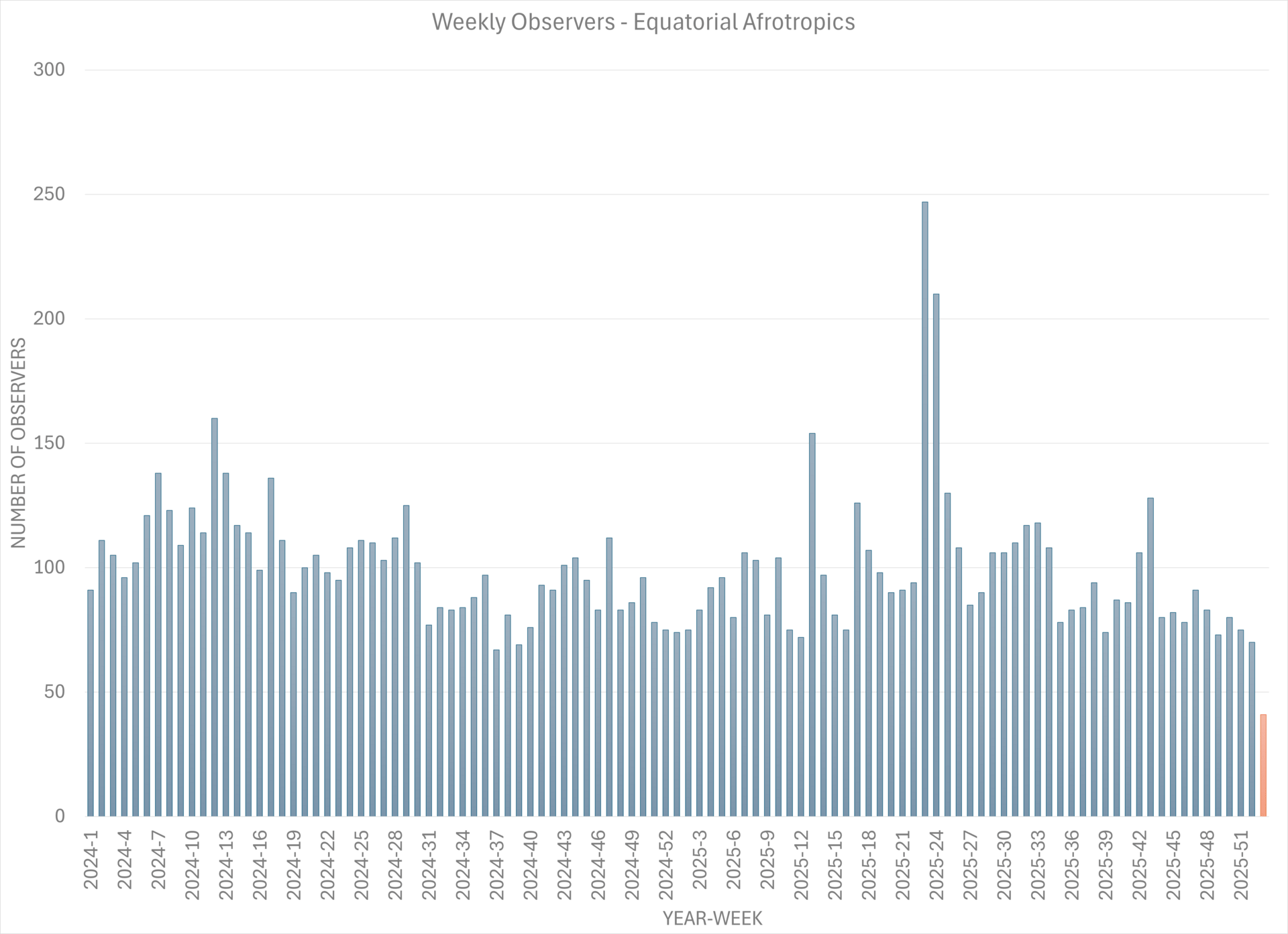

In Week 1 of 2026, we explore the biggest natural events shaping the planet and what millions of iNaturalist observations reveal about life on Earth right now. From the Amazon to the Equatorial Afrotropics, two rainforests on the same latitude tell very different stories.

Global Snapshot

Three forces that shaped the planet last week.

A powerful earthquake in Mexico. On January 2, a magnitude-6.5 earthquake rattled southern and central Mexico, collapsing buildings, triggering landslides, and setting off thousands of aftershocks.

Cyclone winds and rain in northwest Australia. Cyclone Hayley made landfall with intense winds and heavy rain, closing roads, damaging homes, and prompting widespread flood warnings.

Flash flooding in Afghanistan. Heavy rain and snowmelt triggered sudden floods that damaged infrastructure, displaced families, and killed dozens.

And then, three major wildlife events unfolded around the world.

Olive ridley sea turtles nesting in huge numbers along India’s east coast. Hundreds of thousands came ashore at once — one of the largest wildlife gatherings on the planet.

Wet-season life exploding in northern Australia. Monsoon rains triggered mass emergences of frogs and insects, along with breeding waterbirds across the wet tropics.

Peak monarch butterfly overwintering in central Mexico. Millions of monarchs clustered tightly in fir forests during the coldest weeks of their annual cycle.

Global iNaturalist* Report

Global iNaturalist Project Spotlights

Three iNaturalist projects stood out this week for strong participation:

The Russian Big Year Award 2026 - This competition is promoting birdwatching in Russia. A grand prize will be awarded to the participant who makes the most bird species observations during the 2026 calendar year.

Bioblitz Summer 2026-Integramar - The goal of the project is to map the coastal flora and fauna of Brazil during the 2026 calendar year.

The Trees of Spring 2026 - The project is part a University of Tennessee at Chattanooga dendrology class and will focus on the trees, shrubs, and woody vines of Southeastern North America. It runs from Jan 1 - Apr 22nd.

Global iNaturalist Photo Highlights**

Downy Woodpecker - Dryobates pubescens - Massachusetts USA

Eastern Dwarf-Mistletoe - Arceuthobium pusillum - Maine USA

Type of Jewel Beetle - Cyphogastra pisto - Australia

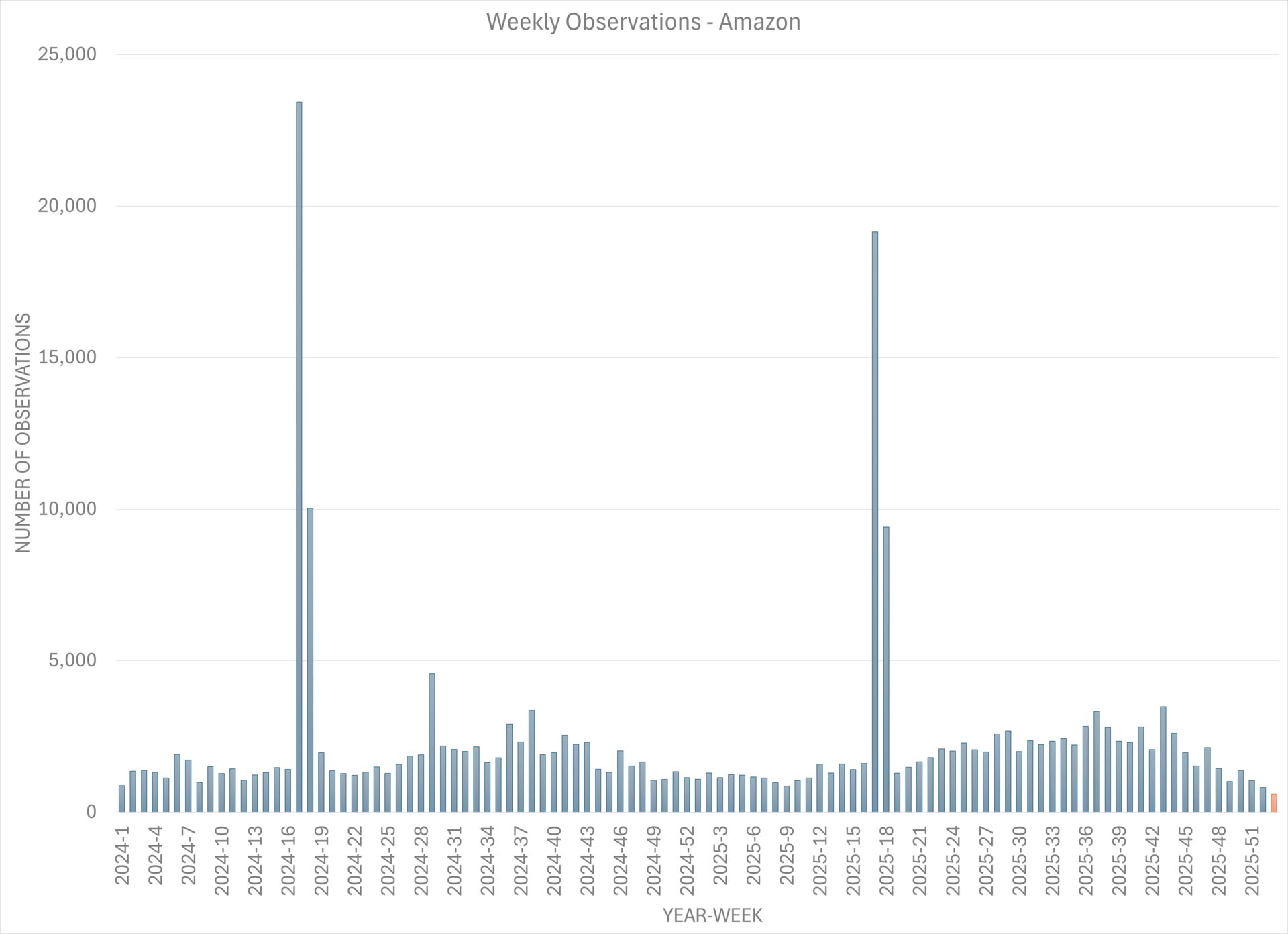

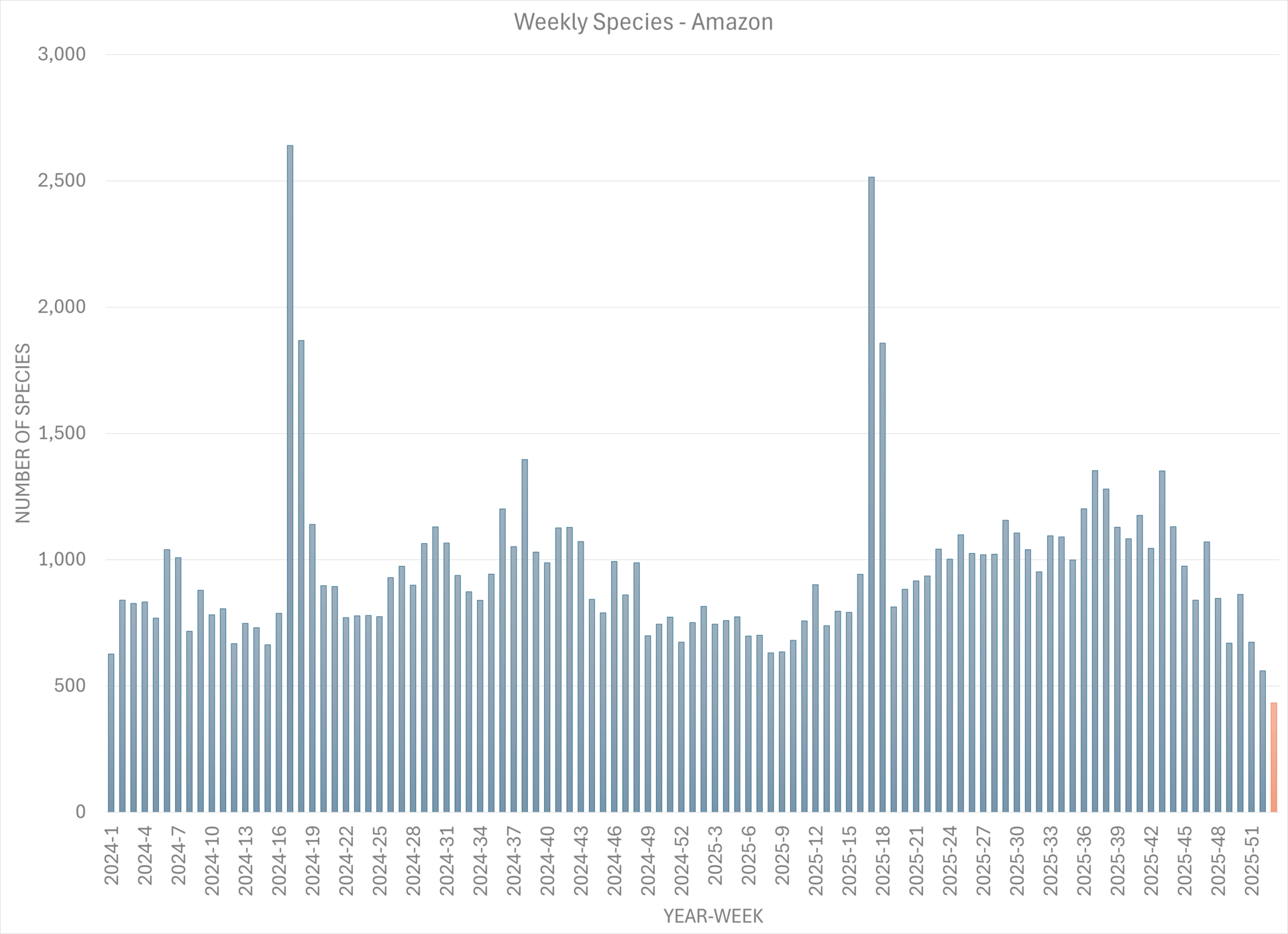

Region 1: Amazon

In early January, the Amazon is deep into its annual rhythm. Three things typically define this moment in the forest.

Peak wet season dynamics. January is firmly within the wet season across much of the Amazon. Heavy, frequent rainfall raises river levels, reconnects floodplains, and reshapes access to vast areas of forest. Water is not just present — it’s moving, spreading, and reorganizing the landscape.

Explosive biological activity. With warmth, moisture, and long daylight hours, plant growth accelerates. Insects emerge in massive numbers, amphibians breed in newly flooded areas, and birds take advantage of abundant food. This is one of the most biologically productive times of the year.

The forest acts as a climate engine. Through evapotranspiration, the Amazon recycles enormous amounts of water back into the atmosphere. In January, this moisture helps fuel regional rainfall patterns far beyond the forest itself — reinforcing the Amazon’s role as a continental-scale system.

iNaturalist Snapshot:

iNaturalist’s users have contributed some great shots:

Type of Begonia - Begonia wollnyi - Bolivia

Type of Ghostplant - Voyria pittieri - Peru

Marsh Deer - Blastocerus dichotomus - Brazil

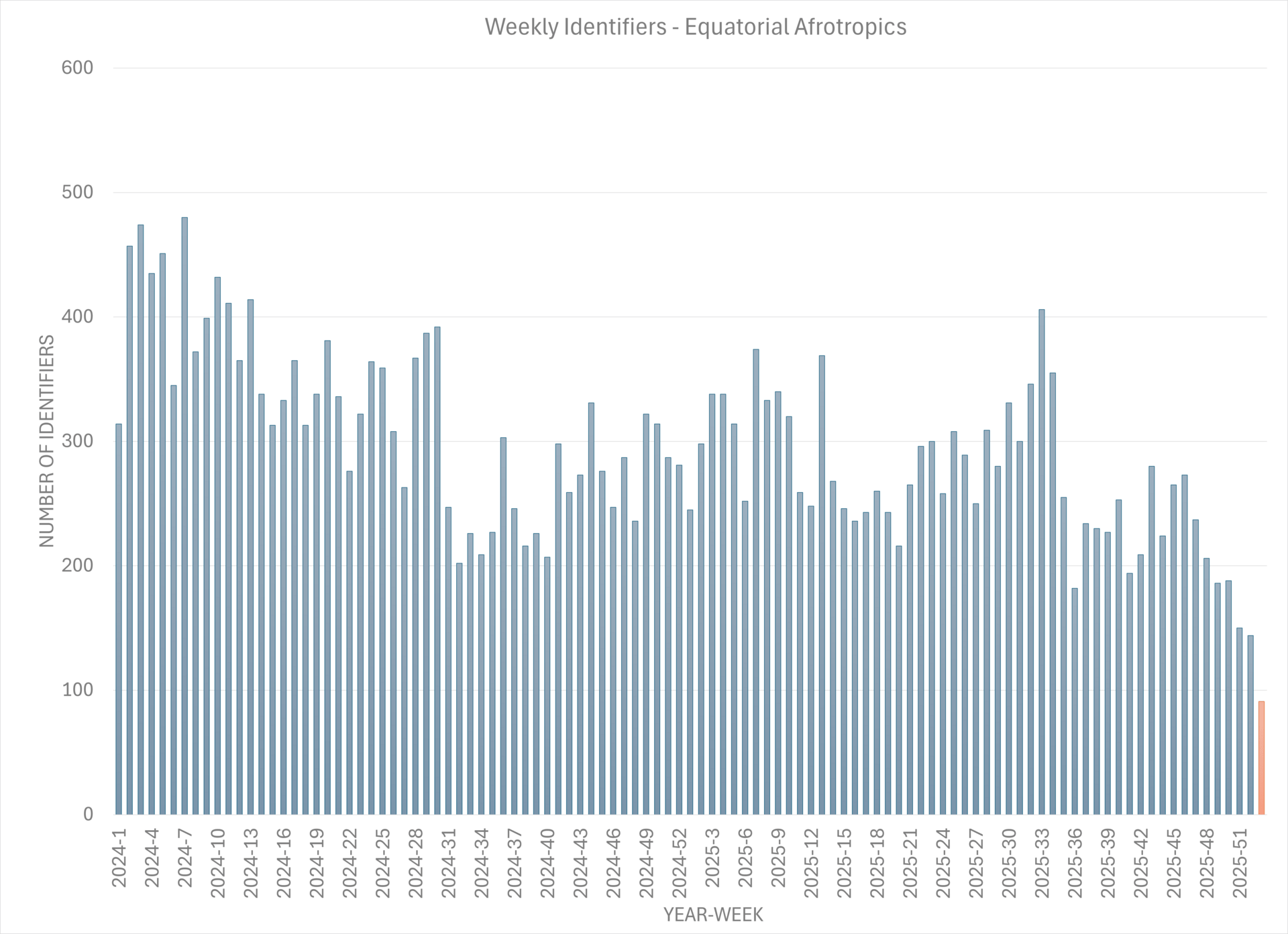

Region 2: Equatorial Afrotropics

In early January, the Equatorial Afrotropics are also following an annual rhythm — but the dynamics are different. Three things typically define this moment.

Equatorial rains with variability. January brings regular rainfall to much of the region, but unlike Amazonia, precipitation is often more spatially uneven. Some areas receive steady rain, while others experience brief dry intervals. The forest is wet — but not uniformly flooded at continental scale.

Wildlife activity is shaped by patchwork landscapes. Warm temperatures and rainfall support high biological activity, especially among insects, birds, and primates. But movement patterns are increasingly shaped by forest fragmentation. Wildlife activity concentrates in intact blocks of forest, river corridors, and protected areas.

The forest is under pressure. This forest still functions as a major carbon and biodiversity reservoir. But in January — as in every season — its ecological processes operate within a landscape influenced by logging roads, agriculture, and expanding human settlement.

iNaturalist Snapshot:

iNaturalist’s users have contributed some great shots:

African Forest Elephant - Loxodonta cyclotis - Ghana

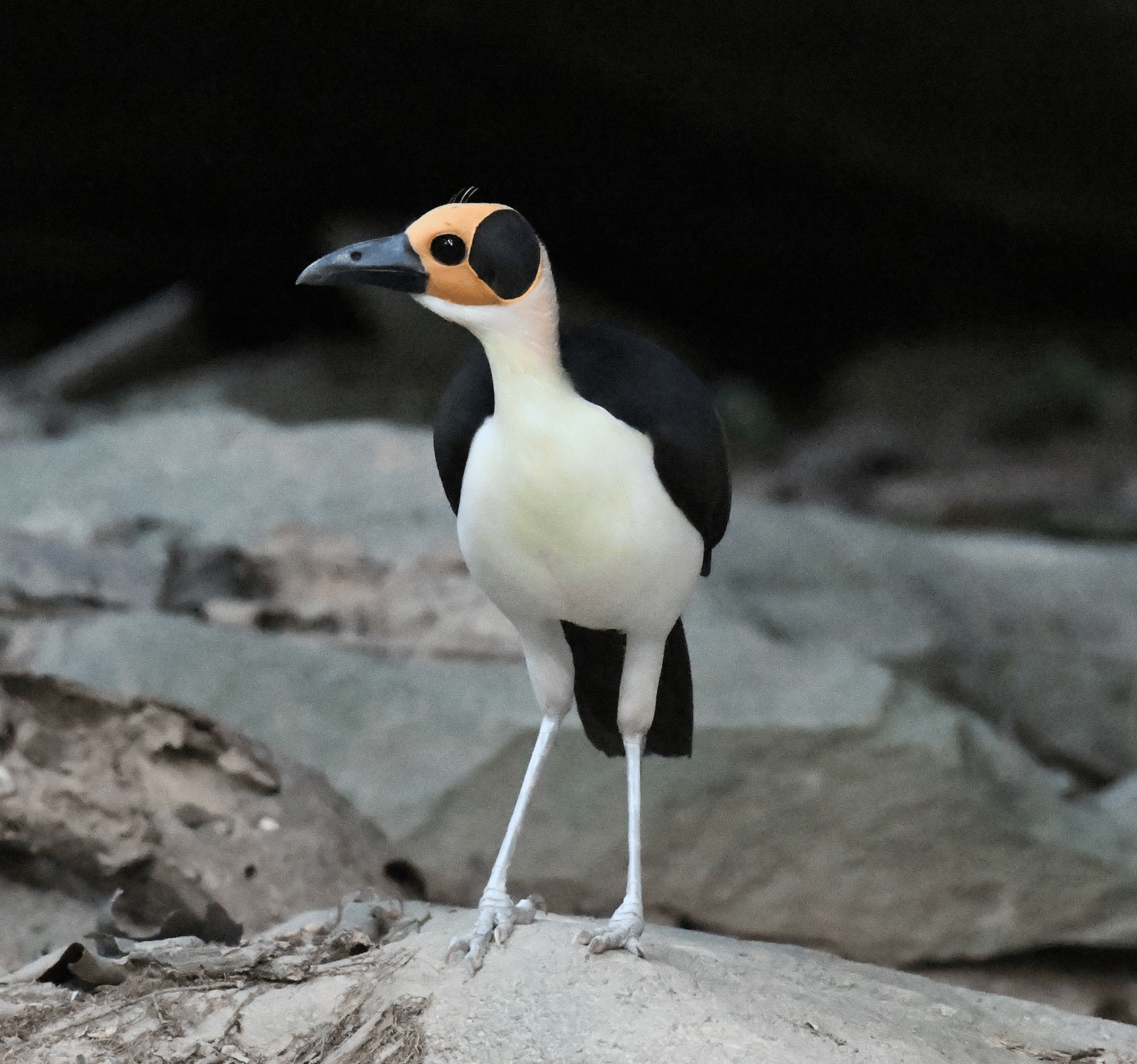

White-necked Rockfowl - Picathartes gymnocephalus - Ghana

Large-eyed Green Treesnake - Rhamnophis aethiopissa - Republic of Congo

Two Rainforests. One Equator

Now that we’ve seen both regions on their own terms, three big points connect and separate these equatorial rainforests.

Continuity versus fragmentation. The Amazon Basin remains the largest continuous tropical forest on Earth. Its rivers, canopy, and atmosphere operate at continental scale. In contrast, the Equatorial Afrotropics still hold extraordinary biodiversity — but much of it exists in a patchwork of intact forest, edges, and corridors.

Ecosystem influence at scale. Amazonia actively shapes climate beyond its borders, recycling moisture and influencing rainfall across South America. The Equatorial Afrotropics also store carbon and regulate climate — but their influence is increasingly regional rather than continental.

Human presence in the system. In both regions, people are part of the landscape — but in different ways. In Amazonia, vast intact areas still exist despite rapidly expanding human development. In the Equatorial Afrotropics, human activity is more tightly interwoven with the forest itself.

Two rainforests. One latitude. One equatorial sun. And very different dynamics

Next week, we step back into an ancient landscape shaped by rivers, stone, and millions of years of life adapting to both. Venezuela The news events of the past weeks matter — but they make more sense when we place them in context.

We'll look at the vast floodplains and waterways of the Orinoco Basin, and the Guiana Highlands, where ancient table-top mountains rise from the forest,

River lowlands. Ancient highlands.

See you next week.

— Naturalists’ World

*This content uses publicly available data from iNaturalist. iNaturalist does not endorse or sponsor this newsletter.

**Some images in this newsletter were shared on iNaturalist under a CC0 (public domain) license. We thank the contributors who generously chose to place their observations and photos in the public domain, helping make global nature education and conservation possible. Individual photographers are not attributed out of respect for personal privacy.